Finding Endurance: When TV historian Dan Snow met the explorers

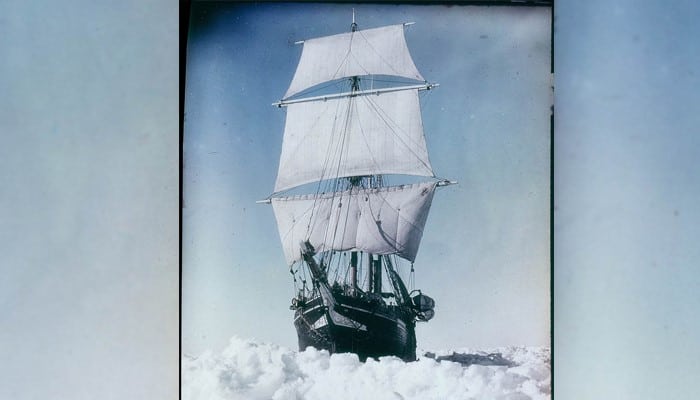

One of the most famous ships in history, the Endurance, has been found 107 years after it sank in the Antarctic during explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton’s doomed voyage.

The vessel was discovered at the bottom of the Weddell Sea, at the northern tip of mainland Antarctica, by modern-day explorers on the Endurance 22 Expedition.

The ship hadn’t been seen since it sank in 1915, after being crushed by sea-ice. Miraculously, Shackleton and the crew escaped unharmed. One hundred years after Shackleton’s death in 1922, the stricken vessel was located at a depth of 10,000 feet.

Initial video footage of the remarkable find, released on 9th March, shows it’s in good condition after being preserved in the icy waters.

Locating the lost ship is a dream come true for TV historian Dan Snow, who was part of the team who found it. He has described the Endurance as “one of the greatest ever discoveries” and “groundbreaking for maritime archaeology”.

When Dan Snow met the explorers and researchers embarking on the Endurance 22 Expedition, none of them knew what lay ahead. After first meeting in South Africa, the team hoped to find the missing ship. However, Snow (famous for presenting TV history documentaries) said they would be vulnerable to storms, ice and very cold climates.

The team was operating from the South African research ship, the Agulhas II. Setting sail on the perilous voyage on 5th February 2022, they were soon surrounded by huge plates of Arctic ice, like those that crushed the Endurance more than a century ago.

Expected to last for at least 35 days, the expedition relied on underwater search vehicles to locate, study and film the Endurance. Finding it after just one month was an unexpected bonus!

Shackleton’s expeditions

Shackleton was 40 when he led the fateful 1,800-mile Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. Two ships, the Endurance and the Aurora, set sail in 1914, each with 28 crew members. Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, gave permission for the expedition to go ahead on 8th August, despite WW1 having begun.

Shackleton, born in County Kildare, Ireland, in 1874, was a Merchant Navy officer in his youth. He spent four years at sea, travelling all over the world. As a young officer, he transferred to the troop ship Tintagel Castle in 1899, during the Boer War.

With a taste for adventure, in February 1901 he joined the National Antarctic Expedition being organised in London by financial backer Llewellyn Longstaff. Shackleton completed two successful expeditions as part of the British Antarctic crew: the Discovery Expedition from 1901 to 1903 and the Nimrod Expedition from 1907 to 1909.

On his triumphant return home, he was a national hero. King Edward VII made him a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order. Later, he was made a knight and became Sir Ernest Shackleton.

Endurance voyage

Shore life didn’t suit him and he yearned for another expedition. He had his chance in 1914 with the launch of the three-year Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition on the Endurance. The voyage was funded privately by business magnates, with help from the British government.

Unfortunately, unlike Shackleton’s two earlier voyages, the third expedition was thwarted by the freezing weather conditions. Departing from South Georgia on 5th December 1914, the Endurance headed for Vahsel Bay in the Weddell Sea. However, the weather gradually grew worse.

On 19th January 1915, deep in the Weddell Sea, Endurance became frozen solid in an ice floe. The ship remained trapped until, on 24th February, Shackleton realised it would be the following spring before they would be freed.

The Endurance became a fixed base until spring arrived in September 1915. However, as the surrounding ice cracked, it put incredible pressure on the ship’s hull. Shackleton had hoped to continue the voyage to Vahsel Bay as soon as the Endurance was freed. However, water began pouring in on 24th October 1915 and he gave the order to abandon ship.

The crew managed to retrieve provisions and equipment to the surrounding sheets of ice and escaped unscathed. The Endurance finally slipped under the ocean’s surface on 21st November 1915.

The men set up camp on the drifting ice floe and endured hazardous conditions for two months. 250 miles from Paulet Island, where more food was stored, they decided to set off on foot, but it was too far. They set up another base, Patience Camp, on an ice floe and hoped to drift towards a safe landing place.

After drifting to within 60 miles of Paulet Island, they were halted by the ice. On 9th April 1916, they had to get into the lifeboats when the ice supporting Patience Camp broke in half. After five days’ drifting at sea, the crew successfully docked three lifeboats at Elephant Island, 346 miles from the final resting place of Endurance.

Shackleton was concerned for the crew’s welfare. He had already suffered frostbite and the chances of being found on Elephant Island were slim, as it was inhospitable and far from shipping routes. He bravely set off on a 720-mile journey to the nearest South Georgia whaling stations in a 20 ft lifeboat, the James Caird, to seek help.

He was accompanied by carpenter Harry McNish, who strengthened the lifeboat and created a makeshift deck; the Endurance’s captain Frank Worsley as navigator; and crew members Tom Crean, Timothy McCarthy and John Vincent. They set sail on 24th April 1916 with a minimum amount of food and water.

After battling stormy seas, in constant danger of capsizing, they spotted the South Georgia cliffs on 8th May 1916, but couldn’t land until 9th May due to a hurricane battering the shore. Shackleton and Worsley then crossed the island by land on a hazardous 32-mile journey, reaching the Stromness whaling station on 20th May.

From there, Shackleton organised the mammoth rescue mission to pick up the three men on the other side of the island and the remainder of the crew from Elephant Island. All were saved and received a rapturous welcome back to civilisation.

Frank Wild, second in command on the Endurance, wrote in his diary that the men were exhausted, seasick and ill with dysentery. He described some as going “insane” with the trauma, but they all made it home eventually.

Sadly, three crew members lost their lives from the Endurance’s sister ship, the Aurora, after it was blown off course and drifted out at sea for many months before finally making it to New Zealand.

Shackleton’s experiences didn’t damage his yearning for adventure and in early January 1922, he launched a new Antarctic expedition. Sadly, he never made it: on 5th January, he died aged 47 of a heart attack while his ship was docked at South Georgia.

Endurance 22 Expedition

The Endurance remained in its icy resting place for 107 years, until Snow and the modern-day explorers followed Shackleton’s historic route and finally found it – four miles from where it had originally sunk. The Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust helped co-ordinate the 2022 expedition, led by Dr John Shears, a veteran polar explorer.

Shears said the moment when cameras filmed the ship’s name was “jaw-dropping”. He described how the Agulhas II had enabled them to complete the most difficult shipwreck search in the world. Like Shackleton more than a century ago, they had battled constantly shifting sea-ice, temperatures of -18°C and blizzards.

Shears said they had achieved what many people thought was impossible. Submarines had combed the search area, checking various targets, before finally finding the Endurance – coincidentally, on the 100th anniversary of Shackleton’s funeral!

Snow and the team have been compiling detailed images of the Endurance, including videos and photographs of its timbers and surrounding debris. The Endurance is officially a monument designated under the international Antarctic Treaty and can’t be moved or disturbed, so no artefacts can be recovered to the surface.

Images show the ship hasn’t changed much since last photographed for the final time by Frank Hurley, Shackleton’s filmmaker, in 1915. The rigging is tangled, and the masts are down, but the hull is largely intact, although with some damage to the bow. The anchors are visible, and the cameras even photographed fascinating signs of the old crew, including abandoned crockery and boots. Shackleton’s cabin is visible through a porthole.

The ghost ship is now home to a diverse selection of deep-sea marine life including anemones, brittle stars, sponges and crinoids.

The 2022 expedition was made possible because during the past month, the lowest amount of Antarctic sea-ice ever recorded since the 1970s was revealed by satellite, so the conditions were extremely favourable.

Share this post

Tags

- Career Development

- Celebrity Meetings

- Conferences

- Confidence

- Exhibitions

- Historic Meetings

- How to Interview Effectively

- Human Resources

- In The Press

- Meetings and Conferences

- Monarchy

- News

- Our Team

- Personal Development

- Personnel

- Presentation Techniques

- Teamwork

- Top Tips for Meetings

- Training & Workshops

- Video Conferences