Historic meetings: When Titanic met with an iceberg

Seldom has a maritime tragedy generated as much interest as the sinking of the Titanic.

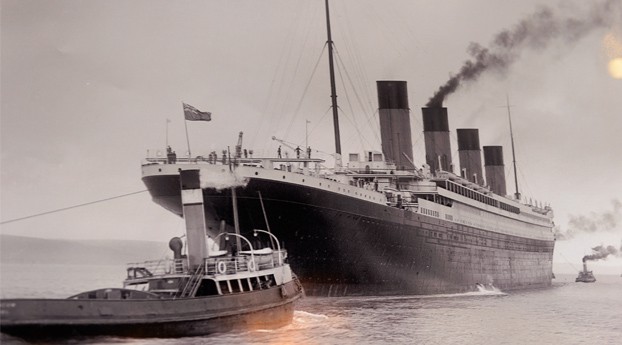

The White Star Line vessel RMS Titanic set sail from Southampton to New York City on 10th April 1912, carrying 2,224 passengers and crew. As a designated Royal Mail Ship, she was authorised to carry mail as well as passengers.

Sadly, on 14th April 1912, the Titanic met with a giant iceberg, estimated to be up to 100ft high and 400ft long. A gaping 300ft long hole appeared in the ship’s hull and the ‘unsinkable’ vessel vanished beneath the North Atlantic Ocean on 15th April.

As the 109th anniversary of the deadliest peacetime sinking of a cruise ship approaches, we’re remembering the human tragedy behind the disaster that has sparked much scientific and scholarly speculation, not to mention multiple books, films and TV series.

Creation of the Titanic

In the early 1900s, transatlantic travel became a lucrative market, not only for the wealthy taking holidays overseas but also for immigrants. The main operators were Cunard and White Star. In 1907, White Star chairman J Bruce Ismay decided to build a new class of large liner, known for comfort and luxury.

Plans for the Titanic, the Olympic and the Britannic were drawn up. Construction of the Titanic began on 3rd March 1909 in Belfast, Ireland, at a cost of almost £5 million, equating to £143 million in modern terms, taking inflation into account.

One of the largest and most luxurious ships in the world, the Titanic was 882.5ft long, 92.5ft wide and weighed a mighty 46,328 tons. Designed by Thomas Andrews, of the Belfast shipbuilding firm, Harland and Wolff, the Titanic featured ornate decorations, a swimming pool, a huge first-class dining restaurant and four elevators.

While the first-class accommodation was opulent, even its second-class suites were comparable with first-class on other vessels. The third-class accommodation was modest, but still relatively comfortable.

Thanks to modern safety features, including 16 compartments with doors that could be closed from the bridge, the Titanic was thought to be unsinkable. Theoretically, the water could be contained, should the hull be breached. Even if four compartments were flooded, this shouldn’t endanger the Titanic’s buoyancy.

It took around 11 months to kit out the interior of the ship to the level of luxury promised to the wealthy passengers. In early April 1912, the Titanic was declared seaworthy after completing her sea trials.

Maiden voyage

Launched on 11th May, the RMS Titanic was supposed to make history as one of the first cruise liners designed purely for luxury and comfort, rather than just speed. Her nickname was the “Millionaire’s Special” and fittingly, the captain was Edward J Smith – known as the “Millionaire’s Captain” because he was much-loved by wealthy passengers.

Onboard were a number of prominent people including co-owners of the famous Macy’s department store, Isidor Straus and his wife, Ida; American businessman Benjamin Guggenheim; British newspaper editor William Thomas Stead; US business magnate and multimillionaire John Jacob Astor IV; White Star chairman Ismay and Titanic designer Andrews. The only one of the seven to survive the tragedy was Ismay, who helped many other passengers to safety, before getting on the final lifeboat himself.

A first-class ticket ranged from £110 (around £1,200 today) for a simple cabin; up to £3,100 (£35,000 today) for one of the two most opulent “Parlour” suites. Second class tickets started at £45 (around £500); and third-class rooms started at £10 (£125 in today’s money).

The Titanic set sail from Southampton on 10th April 1912, stopping at Cherbourg to pick up more passengers. After a two-hour stop, the ship set off for the coastal town of Cobh in Ireland, where more passengers were picked up on 11th April, before setting sail for New York City at around 1.30pm.

Onboard were more than 2,200 people, of which 1,300 were passengers and the remainder were crew. Throughout the transatlantic voyage, the Titanic’s radio operators, Harold Bride and Jack Phillips, received iceberg warnings and passed them to the bridge. The Titanic approached an area known to have icebergs on the evening of 14th April. Captain Smith changed the ship’s course, heading farther south, to try and avoid the area, maintaining a speed of 22 knots (around 40mph).

At around 7.50pm, Stanley Adams, radio operator of the liner Mesaba, sent a message to the Titanic, warning of an ice field. He described seeing “much heavy pack ice” and a “great number of large icebergs” and provided the location. The message was received by the Titanic’s radio room at 9.40pm. Tragically, it was never relayed to the bridge – something investigators have been trying to understand for a century.

At 10.55pm, the liner SS Californian sent a radio message that it had stopped, surrounded by ice, in the same area. Phillips was said to be relaying messages to passengers at the time and the message about the ice wasn’t prioritised. As Phillips died on the Titanic, no-one will ever know why.

Sinking of the Titanic

The Titanic’s two lookouts, Reginald Lee and Frederick Fleet, were perched high above the deck in the crow’s nest, looking for hazards. At around 11.40pm, they saw an iceberg ahead, around 460 miles south of Newfoundland, Canada. They notified the bridge.

First Officer William Murdoch ordered a “hard-a-starboard” manoeuvre, combined with reversing the engines, in a bid to turn from the iceberg’s path. This reversal of direction was common in ships of the era, although is not used much today.

Tragically, the iceberg was too close to avoid a collision. The complex task of reversing the engines would have taken some time to complete. The centre turbine and centre propellor had to be stopped altogether, thus reducing the rudder’s effectiveness.

Investigators later said this had impaired the Titanic’s ability to turn and suggested the ship might have missed the iceberg had she been turned quickly while maintaining forward speed. Turning the ship managed to avoid a head-on collision, but the iceberg met the Titanic’s side with a glancing blow, causing a hole.

At least five of the ship’s supposedly watertight compartments were breached. The designer, Andrews, assessed that the ship’s front compartments were filling with water, causing its bow to start sinking. Water from the ruptured compartments spilled over, gradually filling the whole ship with water and sealing her fate. Today, most experts believe hitting the iceberg head-on would have caused less damage due to the ship’s design.

However, on the night of the accident, no-one could have foreseen the chain of events, as Ismay had reportedly insisted the ship was unsinkable, even as she was struck. Phillips began sending distress signals right away, but the only ship near enough to carry out a rescue, the SS Californian, failed to respond.

Lifeboats launched

Other ships received the distress call, including the Carpathia, at around 12.20am on 15th April. The Cunard vessel immediately set sail towards the stricken Titanic but was too far away and the journey took more than three hours. Another ship that responded, the Olympic, was also too far away.

It was soon apparent the Titanic was ill-prepared for such an accident. Lifeboats were launched, with the order, “Women and children first.” The number of lifeboats complied with the requirements of the British Board of Trade. However, the 20 boats had the capacity to take only 1,178 people – way short of the total number of passengers and crew on board.

In addition, the lifeboats weren’t full when launched, as the crew members were concerned the crane system used to lower them into the water couldn’t support them at full capacity. Unfortunately, the crew were unaware the davits had been successfully tested in Belfast, and the Titanic hadn’t done its planned lifeboat drill earlier that day.

Lifeboat number seven, the first to be launched, contained only 27 people, although it could have carried 65. By the time all the lifeboats had been launched, only 705 people were safely onboard.

Survivors later said the Titanic’s musicians bravely carried on playing to entertain and calm the passengers until the ship went down. Sadly, none of them survived.

By 1am, panic escalated as water flooded into E deck and reached the base of the grand staircase. The radio operator, Phillips, continued to send increasingly desperate distress calls, noting the Titanic “couldn’t last much longer”.

By 2am, the ship’s propellers were visible above the water as she listed and started to go down. Only three collapsible lifeboats remained, and Captain Smith released the crew, saying, “It’s every man for himself.”

The lights went out at 2.18am and the ship broke in two, with one part sinking within six minutes and the other beginning its final plunge soon afterwards. Hundreds of passengers and crew were left swimming in the icy water and almost all of them died from exposure.

More than 1,500 people perished, with the worst casualties being in third class, where only 174 of the 710 passengers survived. It was reported some had been unable to navigate the complex layout of the Titanic from the lower levels as they filled with water, so the lifeboats had gone by the time they reached the top deck.

Rescue operation

The Carpathia was the first rescue ship to arrive at around 3.30am and over a period of several hours managed to pick up all the survivors.

Ismay sent a message to White Star’s offices expressing his “deep regret” at the sinking of the Titanic, reporting “serious loss of life”. The Carpathia docked at New York City on 18th April, at around 9am, with the survivors, who were greeted by a large crowd.

During the subsequent investigations, the Californian’s captain, Stanley Lord, was criticised for failing to react quickly enough, as this would have meant a “different outcome of the tragedy”. The ship’s radio had been turned off for the night, so the captain didn’t receive the message until too late.

Lord spent the rest of his life trying to clear his name and refuting the findings, although no charges for negligence were ever brought against him. Ismay sank into a deep depression and never recovered. He died in London in 1937, at the age of 74.

After many meetings at the highest level to discuss the disaster, a report was presented to the US Senate on 28th May 1912. Along with the findings of a British inquiry later the same year, the recommendations led to changes in maritime safety procedures.

Share this post

Tags

- Career Development

- Celebrity Meetings

- Conferences

- Confidence

- Exhibitions

- Historic Meetings

- How to Interview Effectively

- Human Resources

- In The Press

- Meetings and Conferences

- Monarchy

- News

- Our Team

- Personal Development

- Personnel

- Presentation Techniques

- Teamwork

- Top Tips for Meetings

- Training & Workshops

- Video Conferences